The Greatest Moat Ever: How Bloomberg's Terminals Conquered Finance

When Information Becomes More Valuable Than the Money It Tracks

"Whoever controls the flow of information controls the world."

George Orwell

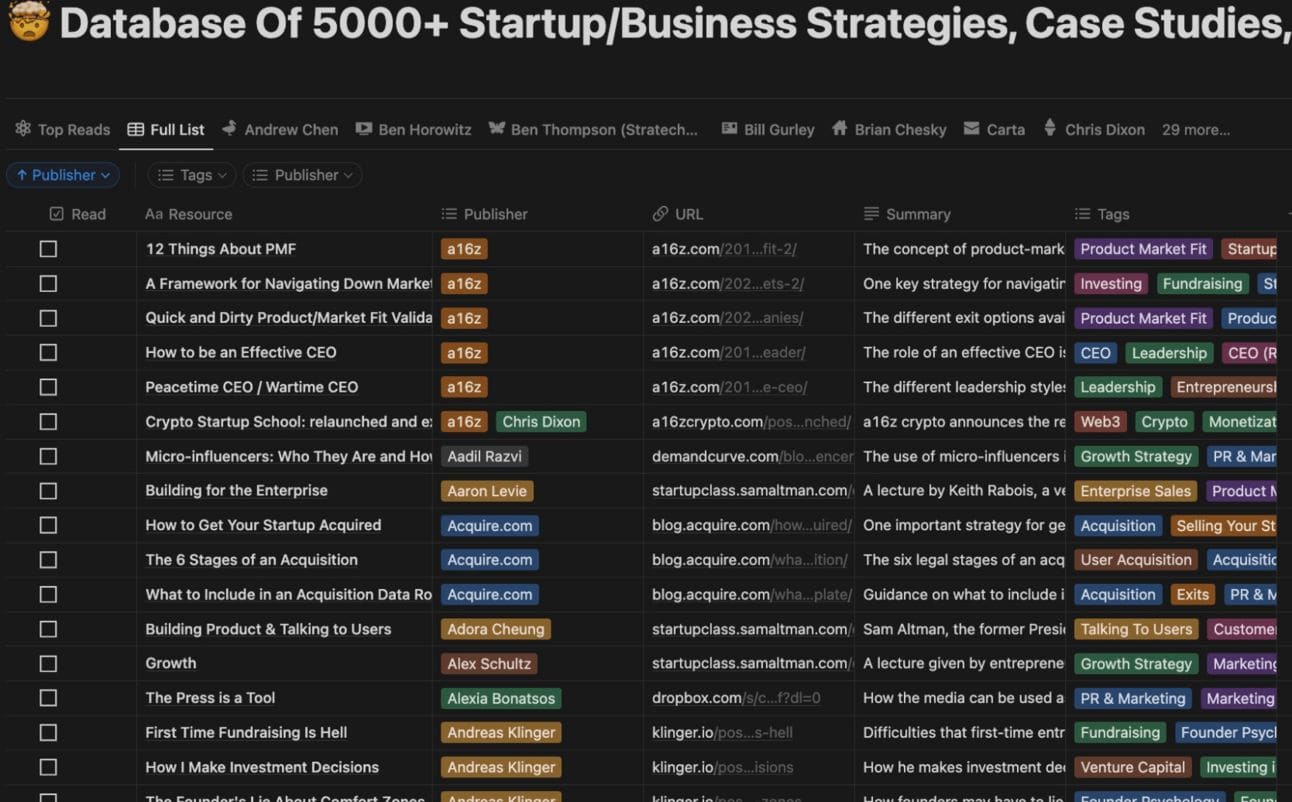

Our friends at the Strategy Arch Newsletter have a great (and free!) offer for our readers:

Database of 5347+ Startup/Business Resources

Get access to this massive database of the best 5347+ Startup Resources, the Best 50+ Ads of All Time, and 900+ Pitch Deck Libraries for free.

You can get them here in one click- https://thestrategyarch.beehiiv.com/subscribe

On August 2, 1990, Iraq invaded Kuwait.

Oil prices reacted harshly, and increased by 33% in a single day.

The Dow Jones Industrial Average fell by 6.3% in the week following the invasion.

Global markets lost approximately $1 trillion in value in the initial market reaction. This resulted in U.S. Treasury yields fluctuating dramatically, with the 10-year yield dropping from 8.3% to 7.5% in the weeks following the invasion as investors sought safe havens. Trading volumes in bond markets increased by approximately 40% during this period.

While most traders scrambled for information, Merrill Lynch's bond desk had a critical advantage. Using their Bloomberg Terminals, they could instantly see how geopolitical events were affecting bond prices across different markets.

Michael Bloomberg, recounting this period years later, noted how his terminals—just nine years after founding the company—had become indispensable in moments of market volatility. "Our subscribers could see the instant correlation between oil prices, treasury yields, and currency movements," he explained in his memoir. "Information wasn't just power—it was survival."

The terminals weren't just providing data; they were delivering a comprehensive view of market reality when it mattered most.

Trading is always an information game. Whoever has the fastest and most reliable data has an enormous advantage on Wall Street. Nowadays hedge funds are pouring millions on overseas data centers, trillion GB data, or even weather forecasts to gain a millisecond advantage, this game belongs to one company only.

One can even say that the game was invented by the company.

Dear reader, welcome to the amazing story of how one company created a monopoly in the middle of our financial system.

What is Bloomberg?

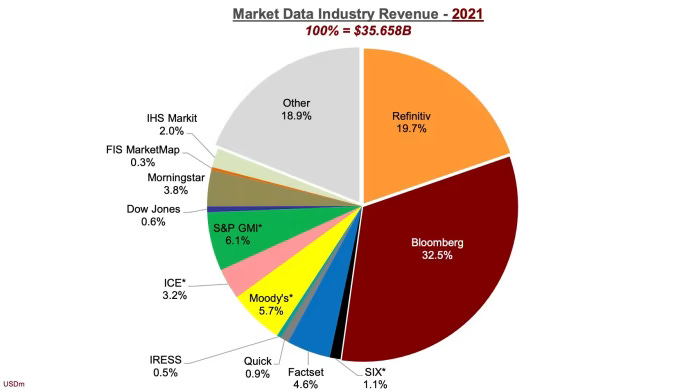

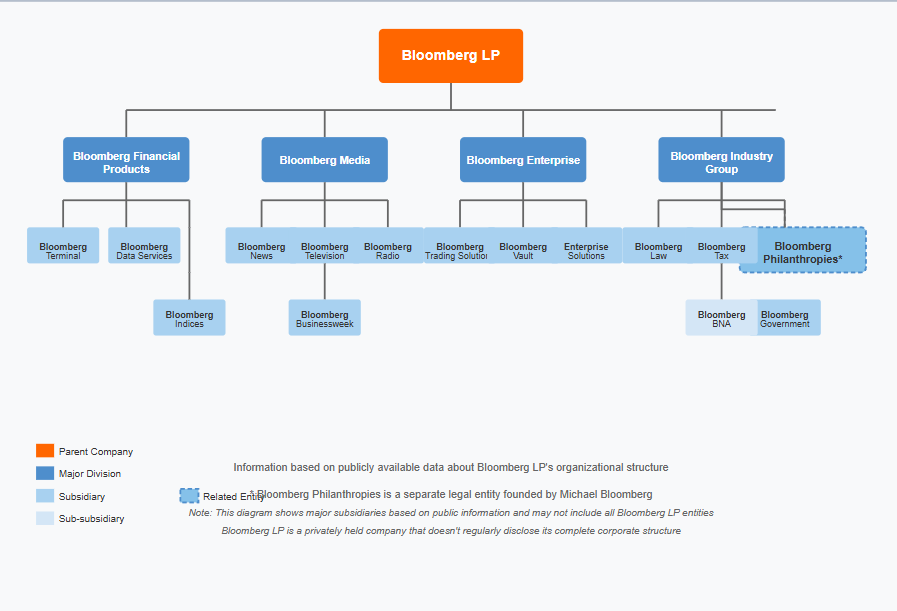

Founded in 1981 by Michael Bloomberg, Bloomberg L.P. is a financial information and media company best known for the Bloomberg Terminal—a computer system providing real-time financial data, analytics, news, and trading tools to financial professionals. The company has expanded into a media empire including Bloomberg News, Bloomberg Businessweek, and Bloomberg TV, while maintaining its core business of premium financial information services that generate over $10 billion in annual revenue.

The Information Desert: When Wall Street Operated in the Dark

In the late 1970s, Wall Street faced a paradoxical problem: despite being the global epicenter of finance, it operated with shockingly poor information infrastructure. The financial landscape was characterized by:

Bond traders relying on paper tickets and phone calls to discover prices (yes, those chaotic scenes where everyone is shouting to everyone)

Market data arriving with significant delays, sometimes hours old

Critical information siloed within institutions or individual paper records

Research buried in physical documents with limited circulation

Analytics performed manually or on primitive computing systems

For the average trader or investor, obtaining accurate, timely information was a constant battle. Major financial institutions maintained information advantages through size and relationships, while smaller players operated at a significant disadvantage.

The conventional wisdom was clear: information asymmetry was a feature of markets, not a bug. Those with privileged access to information enjoyed an advantage that translated directly into profits.

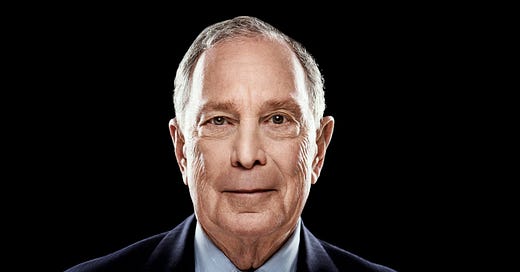

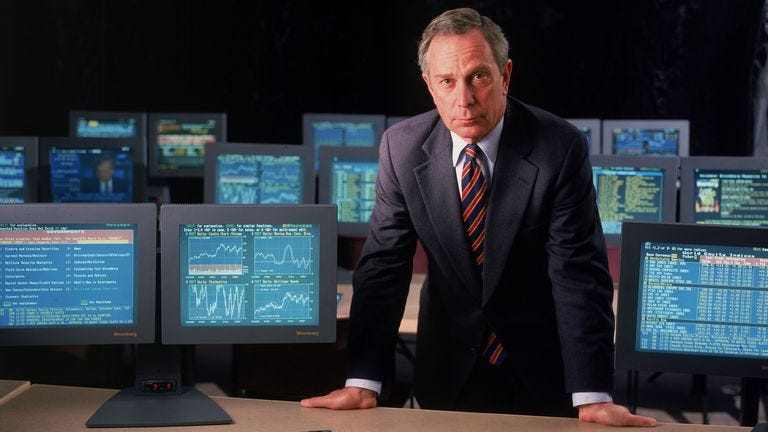

The Vision Builder: How Michael Bloomberg Saw Opportunity in Transparency

Michael Bloomberg's path to creating an information empire was neither direct nor obvious. After being fired from Salomon Brothers following its acquisition in 1981, Bloomberg took his $10 million severance and made a bet that would put him among the most powerful people in the world.

Bloomberg had worked at Salomon Brothers since 1966, rising through the ranks from a lowly clerk counting bond certificates in the vault to become the head of equity trading and sales. This journey gave him intimate knowledge of Wall Street's information problems. As he would later recall: "I understood that on Wall Street, information was money—but only if you had it before others, could organize it better than others, and could leverage it faster than others."

His insight wasn't simply that information was valuable—everyone knew that. His revolutionary perspective came from recognizing three critical truths:

The value of organized information exceeded raw data. Simply having numbers wasn't enough—context, analytics, and usability were what created premium value.

Technology could standardize financial information. Customized, proprietary systems could organize chaotic financial data into standardized formats usable across institutions.

People would pay premium prices for reliable, real-time data. Information wasn't just another commodity—it was the fundamental resource upon which all financial decisions depended.

With these insights, Bloomberg founded Innovative Market Systems (later Bloomberg L.P.) and created the Market Master terminal—which would evolve into the Bloomberg Terminal. The first customer was Merrill Lynch, which ordered 20 terminals and invested $30 million in the startup.

The Billion-Dollar Blueprint: Creating a Premium Information Ecosystem

Bloomberg's story reveals profound principles about premium value creation that extend far beyond financial data:

1. Important Problems = Higher Prices

The Bloomberg Terminal now costs approximately $24,000 per user annually—a price that has remained remarkably stable despite technological advances that have dramatically reduced costs in other information sectors.

Why can Bloomberg maintain this premium? Because the depth of the problem it solves—immediate access to comprehensive financial information—directly impacts billion-dollar decisions. Financial professionals don't merely want this information; they fundamentally cannot perform their jobs without it.

The more essential a problem solution is to high-value decisions, the more premium you can command.

2. Ecosystem Over Product

Bloomberg didn't simply create a product; it built an ecosystem. The Terminal evolved from a data display into a comprehensive platform including:

Real-time market data across virtually all asset classes

Sophisticated analytics and trading tools

Secure messaging between market participants (Bloomberg Chat)

News targeted specifically to financial decision-makers

Directory services connecting the financial community

This ecosystem created powerful network effects—the more people used Bloomberg, the more valuable it became for everyone in the network. This created a moat against competitors who might offer individual features at lower prices.

Building interconnected systems creates more sustainable premium value than selling isolated products.

3. Interface as Premium Marker

Paradoxically, the Bloomberg Terminal's user interface has maintained an intentionally distinctive design that defies conventional user experience principles (unfortunately it is ugly as hell tho). The system uses a specialized keyboard with colored function keys and a dense, information-rich display that appears outdated by consumer technology standards.

This wasn't a failure to evolve but a deliberate strategy. The distinctive interface became a status marker in the financial world—a signal of professional belonging. Mastering the Bloomberg Terminal's shortcuts and commands became a form of specialized knowledge that separated insiders from outsiders.

Deliberate friction creates value by signaling expertise and establishing cultural boundaries.

4. Media as Premium Extension

Bloomberg made a counterintuitive move by expanding into media businesses, including:

Bloomberg News (1990)

Bloomberg Television (1994)

Bloomberg Businessweek (acquired 2009)

While these ventures might appear to commoditize the very information Bloomberg sold at premium prices, they actually strengthened the core business by:

Establishing Bloomberg as an authoritative information source

Creating broader brand awareness that reinforced premium positioning

Generating content that added value to Terminal subscriptions

Building relationships across the business and financial ecosystem

Vertical integration into a sector can deepen your moat.

Mining for Gold: Finding Your Bloomberg Opportunity

So for non-finance folks, how can you apply these principles to create premium value in your own contexts?

Identify critical decision points. Where do professionals face high-stakes decisions with inadequate information? The higher the stakes, the greater the premium potential.

Create order from chaos. Industries drowning in disorganized data present opportunities for premium solutions that transform information overload into actionable intelligence.

Build network effects. The most defensible premium positions come from platforms that become more valuable as more people use them.

Create specialized languages. Systems that require specialized knowledge to use effectively can create premium through exclusivity and professional identity.

Look for information asymmetries. Markets where information is unevenly distributed often hide premium opportunities for those willing to increase transparency—at a price.

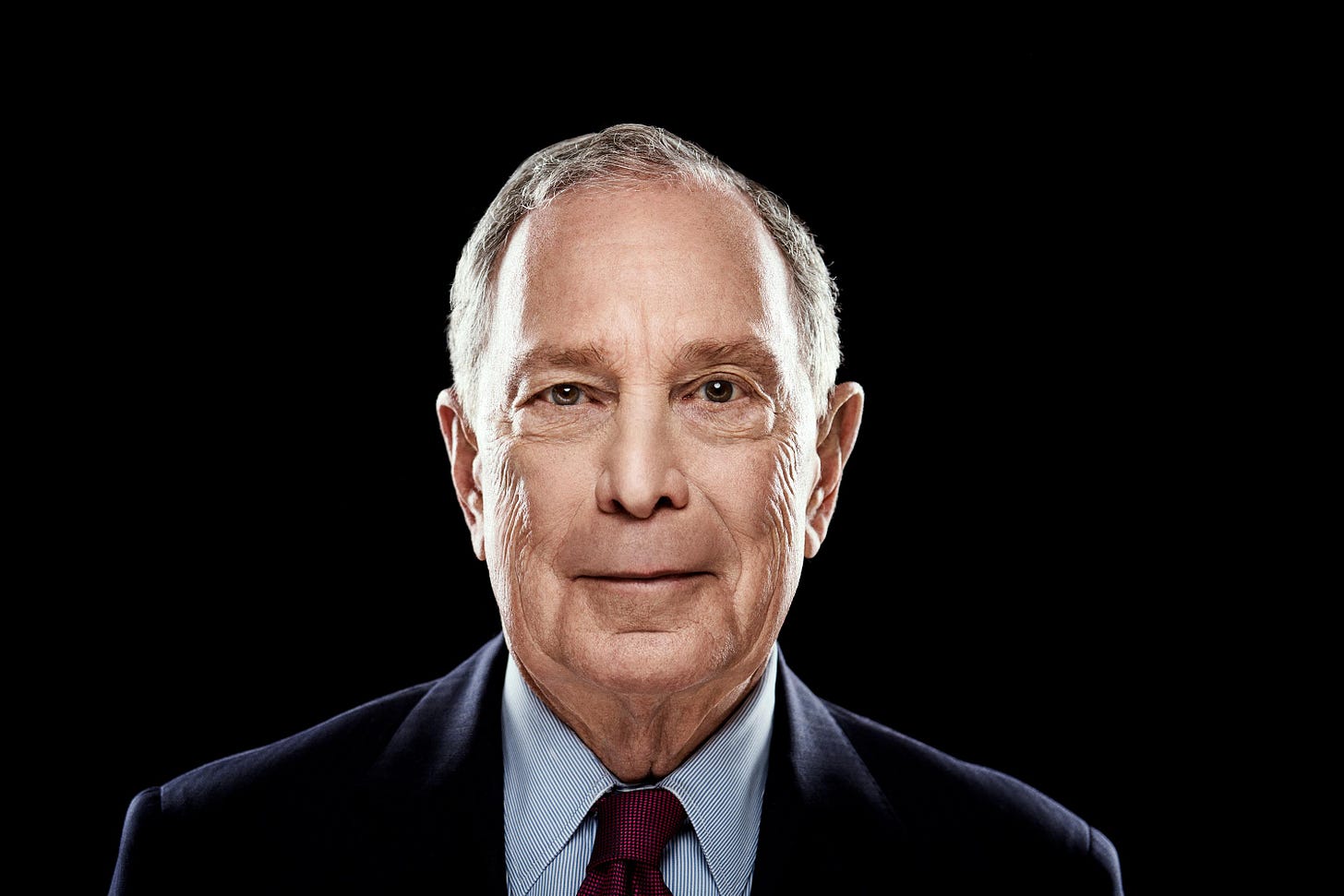

The Deeper Meaning: The Man Behind the Machine

Michael Bloomberg's story reveals a deeper truth about premium value creation: personality and principles matter. His leadership approach—combining technical vision with commercial pragmatism—shaped Bloomberg's premium positioning in several critical ways:

Conviction in value. Bloomberg famously refused to discount his product, even when facing rejection. This pricing discipline communicated unshakable confidence in the Terminal's value.

Meritocratic culture. The company's famously demanding culture—including the controversial open office plan where even the founder sits—reflected Bloomberg's belief that excellence justifies the premium.

Reinvestment philosophy. Unlike many founders, Bloomberg continuously reinvested profits into improving the core product rather than diversifying into unrelated businesses, maintaining the premium quality of the core offering.

Customer immersion. Bloomberg regularly visited clients personally, maintaining direct connections with users that informed product development and reinforced the company's commitment to its customers’ success.

After building his information empire, Bloomberg took his approach to problem-solving into politics, serving three terms as Mayor of New York City (2002-2013), where he applied data-driven approaches to urban governance. He later returned to lead his company, demonstrating his continued commitment to the business he built.

Perhaps most tellingly, when Bloomberg (the man) considered selling Bloomberg (the company) in 2013, the estimated price was $40 billion—extraordinary value created from solving a fundamental information problem.

Just like we highlighted in the last edition - Profit through Purpose - solving fundamental problems better than anyone else creates a moat so unassailable, that the business becomes a natural monopoly.

A lesson that extends far beyond financial terminals to any business seeking to escape commodity competition. So anyone building and growing a business should reflect on the question once again: What fundamental problem I am solving?

Until next time,

BA

Would you like to collaborate with the Founder Marketer? You can get your brand in front of +15,000 founders and entrepreneurs.